Berlin Winter. By 4 PM, the sun has already set. Even in the daytime, everything is cloaked in shades of gray. Outside the window, the trees stand dark and dense, like water-soaked charcoal. Their thin branches intertwine, revealing their tangled stories. Through them, the sky seeps in, and so does the sunset.

Year after year, I learn how to endure winter. A walk in the forest gives me strength for a week. Inviting friends over to share a warm meal grants me enough warmth to last a month.

This winter solstice, I will make red bean porridge. I will gather people, and together, we will read poetry and dance through the night.

*

“I’d like to invite you to my new home. Most of the words you’re reading here were written in this very place.”

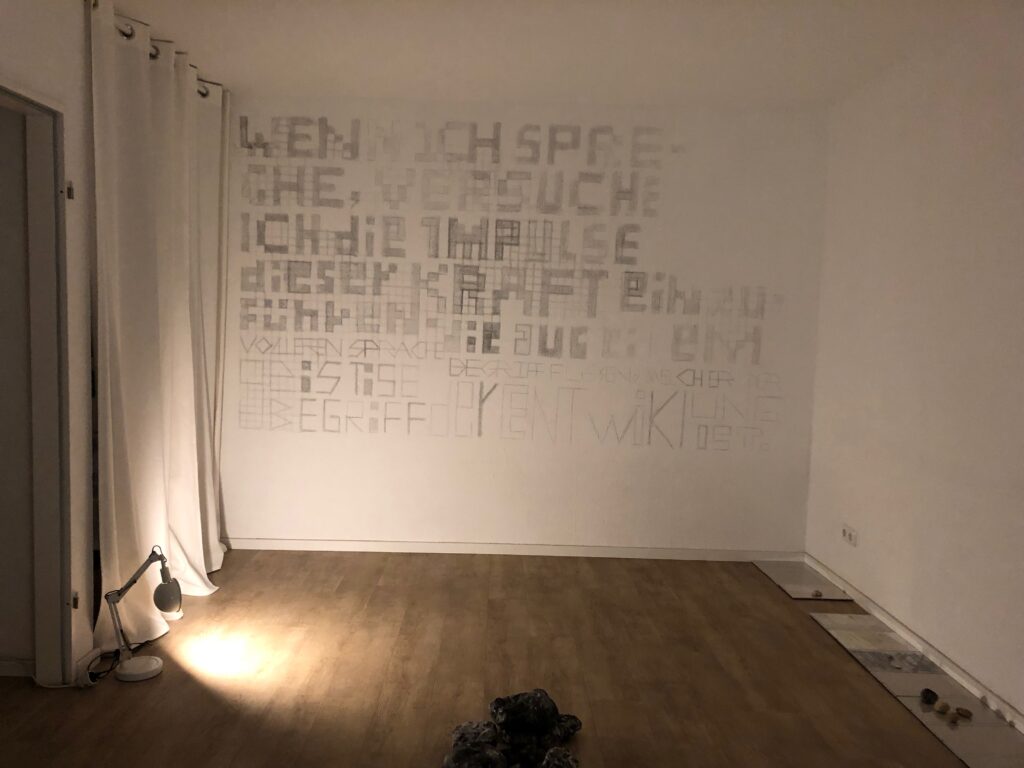

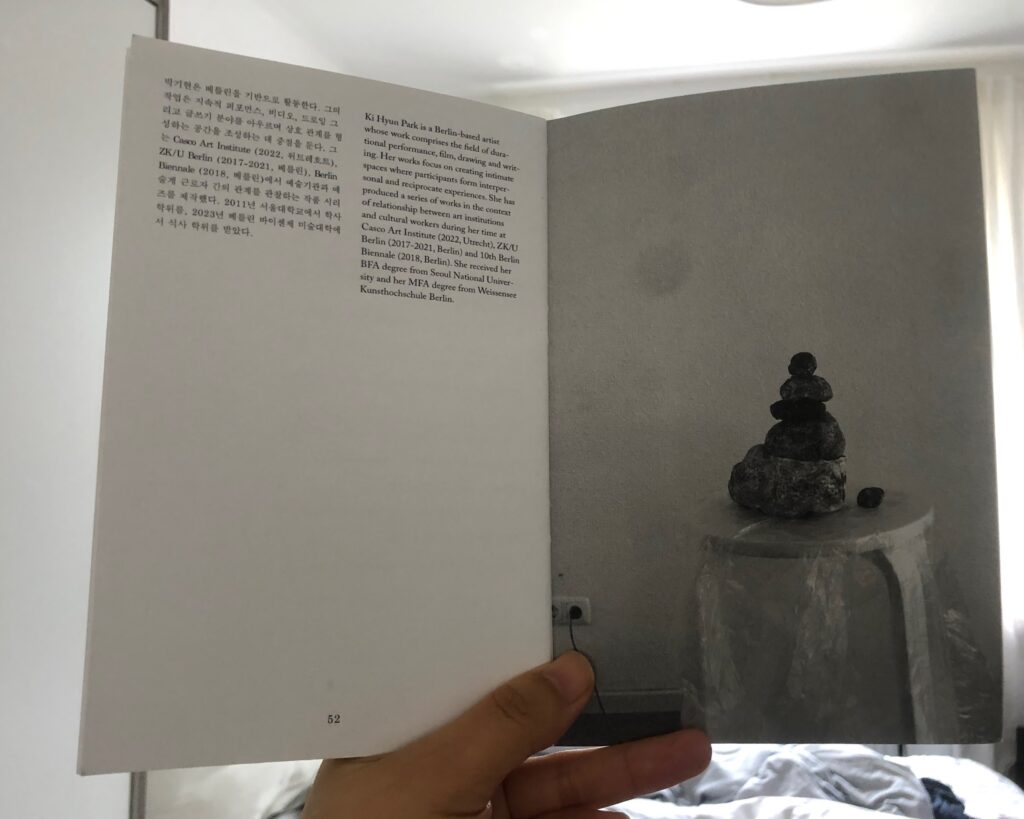

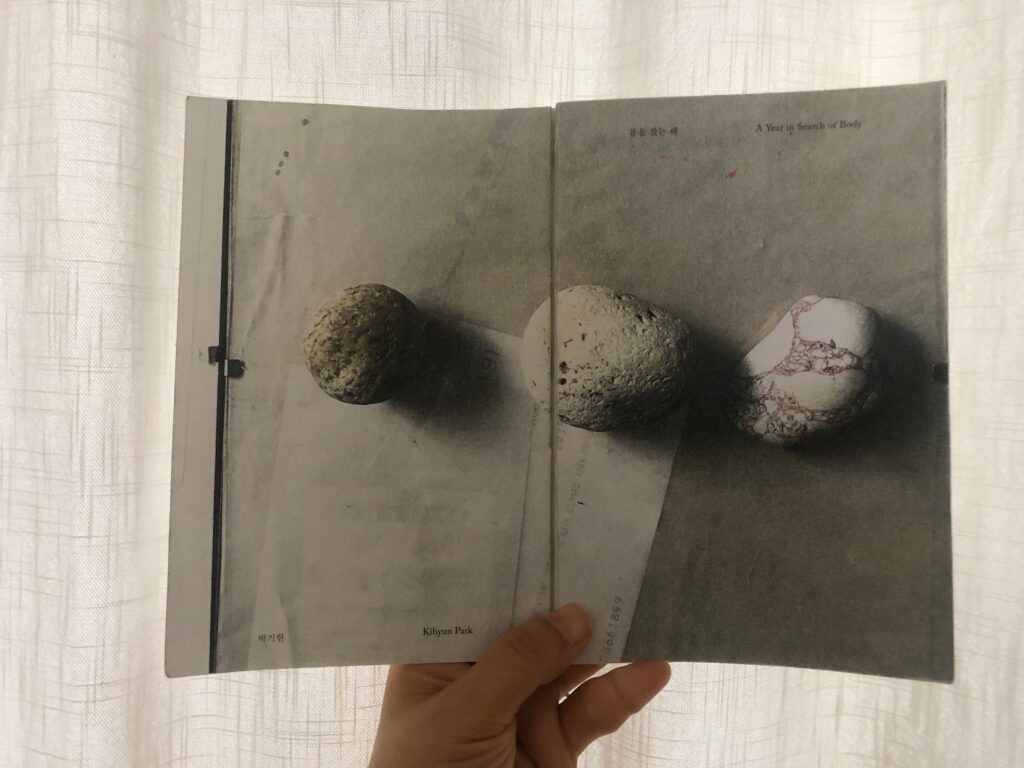

It was on Instagram that I heard about Kiki’s exhibition <A Year in Search of Body>. Next to the invitation, there were images of a neat stone tower and pebbles resembling bird’s eggs. Inviting an audience into one’s home. Transforming a living room into an exhibition space instead of relying on institutions. Turning a private space into a public one. Blurring the boundaries between art and everyday life. The thought alone had always excited me, but knowing that someone was actually doing it made my heart race. I contacted the email address, arranged a visit time, and received her home address. Moon accompanied me.

She said she has been living in Germany for 10 years. There was a large sofa on one side of the living room connected to the bedroom. A long row of books stood along the wall. Since the titles were facing the wall, it looked like a tower of papers in various stages of fading.

The boundary between what was part of the artwork and what was not was unclear. I walked carefully. So that the shape of the stones piled up in the middle of the room does not collapse. It was the stone tower I saw in the invitation post that had the appearance of a coiled creature or a landscape painted in ink wash. Unlike me, who was cautious, Moon sat in front of it and asked, “What material is this?” He asked innocently. In response to that question, Kiki lifted the stone at the top.

“It’s made of clay.” She answered and placed the remaining stones on the floor one by one. About ten stones, both large and small, were easily dismantled. It was quite a surprising transformation.

I wondered, ‘Can it be restored to its original form’, ‘The artist must already know the best combination and its order,’ but then, I thought, ‘There was no precise order from the beginning,’ and ‘There was no fixed form or shape.’ I was taken aback by the fact that the compulsion to order operates even in a disorderly person like me.

Every time a new foot steps on the stone tower, it would build up and collapse in a different shape. I imagined the scene of those soft masses of clay bodies falling and rising over and over again, like a time-lapse video.

When asked, “Would you like a cup of tea?”, I replied, “If it’s okay, I’d love a cup of coffee, please.”

Before heading to the kitchen, she handed me a small booklet, saying, “It would be good to look at it along with the works.” Invitation, images of works, diaries, and poems were all intertwined. Kiki called it a thesis. While the clattering sounds came from the kitchen, we viewed the artwork as if touring a house, reading papers that resonated with the space yet stood independently.

In the corner of the room, I found pebbles. The booklet explained that they were stones Kiki’s late grandmother had kept in a drawer. It felt as though a breath was resting in the small hollows carved into the white stone’s surface. Thinking about the migration of stones and the inheritance of stones, I began to understand why hard pebbles looked like warm bird eggs. I cherished the way the stone fit in my hand, like a fist gently closing around it.

Much of the writing in the paper had already been seen on Instagram. In a sense of déjà vu, I was reminded of the unique intimacy of online spaces.

However, even in that space, Kiki is never reduced to a fixed, singular face.

Based on her experience working in art institutions, she has been carrying out a project called “Body and Institution” for several years. In an online photograph, Kiki is painted green and purple, wearing a flipped wig, and making a playful, provocative expression. Sitting in a yoga pose, she chants, “inhale reality, exhale racism.” In this way, she positions her body as an Asian woman within a structure, revealing and twisting the dynamics between body and institution. What truly drew me here, however, was my curiosity about how the artist, who cleverly exposes social structural inequalities, can simultaneously possess a poetic imagery that captures the resonance and lingering echo of a paused moment.

The paper conveys that Kiki, who used to meticulously plan her work, splitting time tightly to focus on production and exhibition, experienced burnout when she could no longer function. The first thing she did after becoming ill was to put her grid-style scheduler in storage. The current state she presents is one of resistance through stillness after that collapse, an artistic practice that involves rediscovering the lost body.

*

An exhibition for just one person. I thought it was similar to The River I, a performance for just one person. But the one who touched that memory first was Kiki.

“How was that performance on the Spree River back then?”

I was wondering how she knew, but then I remembered that I also posted that day’s records on my Instagram story. To be exact, it is an exhibition and performance to which one or a couple is invited at one time.

At that time, I asked Gabi, who was studying critical dance study with me, to accompany me. Gabi, who came from Costa Rica, was writing a master’s thesis on the theme of water. When she presented the topic, <Bodies of Water: The Possibility of Micropolitical Resistance in Somatic Practices>, I found myself nodding in agreement. Flowing and embracing every place without resisting or forcing her own capacities, Gabi resembled the very shape of water. Whenever I see works related to water, I can’t help but think of her.

Gabi, who holds a bachelor’s degree in dance and psychology, engages in somatic practices that do not separate the body from the mind, but instead approach movement as a process of sensing, perceiving, and experiencing. Her face, as she dances, is calm like a deep well. Her gaze embraces both what is near and far at the same time. It is not an act of self-indulgent narcissism but a gesture that recalls the body’s layered memories and questions the reality of the ground we stand on. The dance of fluidity that Gabi explores does not emerge from a vacuum. It begins by interrogating colonialism and capitalism, which have caused the pollution and severance of water, and the inequality of access to it.

Even without the reminder that over 70% of our bodies are made of water, the body is part of nature — it is nature itself, a complex system. Dancing while listening to the body’s tides becomes a connection to what has been damaged, a gesture of mourning that resists disrupted flows, and at the same time, a practice of care that points toward the possibility of socio-ecological resilience.

“There was nothing. Nothing really. At dusk, the performer put us in a boat and took us to the middle of the river. And all I did was stay on that boat for an hour. Still, it was really good.”

Just thinking about it made me feel like I was back in the calmest moment of a whirlwind year. “I think that was the best moment of the year.” I said softly once more.

Kiki, who was quietly listening, said that she had a moment like that too. “She told us to count to three—‘One, two, three!’—then move to the place of the happiest moment, and afterward close the door and step out again.”

Whether it was therapy, a workshop, or just a casual conversation, I couldn’t quite remember.

“Before I came to Berlin, I lived in Leipzig. There are many lakes there. Perhaps because of the East German culture of swimming naked, everyone takes off their clothes and swims without any hesitation. Every summer, my friends and I visit our own lake. I really enjoyed the time I spent floating in the water with my bare body. If I had to choose the happiest place, for me it would be that lake. That moment when I was floating on the water.”

Kiki said.

*

“Liebe sanghwa. I’m listening to an interview with Shannon Cooney right now. I’m thinking of you. And I’m recalling the performance at the Spree River. My godmother, who is also my aunt, passed away yesterday. I’m grieving and feeling sorrow. The time we spent together on the boat was truly a gift. I remember the water, the sunset of that day, and the moments of farewell.”

It’s a message from Gabi.

Shannon Cooney is a choreographer who deals with the fluidity of bodies and I also met her at an interview requested by Gabi. That day, Shannon said, “Perhaps the flow of water is for the sake of stillness,”, and every time I see moving water, I think of those paradoxical words.

Becoming an audience of The River I was on a long June day. Around 9 PM, on the riverbank, the performer introduced herself as Zinzi and handed us a headset. Zinzi took us onto a wooden boat and, like a messenger, rowed us to the middle of the river. Later, I found out that Shannon was also one of the performers rowing the boat for that performance.

Through the headset, stories of rivers, song, humming, and silence flowed. For an hour, I listened to the river’s song.

However, what I looked at while lying on the boat was not the river, but the rolling sky. Birds swam above it like a school of fish. The world I looked up at from the middle of the river was filled with movement, light, sound, and life. I thought the boat that carried us was like a cradle, but since I had never had a memory of a baby crib, I instead remembered the village I was born in, the creek, and the faces of my older and younger sisters surrounding me.

*

“Liebe Gabi, I express my deepest condolences. I often think about that day too. How beautiful and grateful that moment was. Since then, my younger sister has remained ill, and she’s only getting worse. Life is full of joy and, at the same time, full of sorrow. I can only be grateful for what is given to me now.”

answered Gabi.

It was around that time when I first heard the news about my youngest sister. Just before the summer solstice, when everything was bathed in light and green, when the season itself was in the midst of a grand festival—my youngest sister had collapsed. My three sisters gathered at my eldest sister’s house.

Being far away, I suggested we exercise together via video call. That’s how our little ritual began. At noon, it connects with the evening scene in Korea. My mother and the four sisters gather in the small screen. We breathe together and do yoga. Just as we’re about to finish, my eldest sister and the third one get up and start dancing wildly. We all burst into laughter at their movements. As my youngest sister was leaving, she sent a text message.

“Sometimes, I used to wish we could all live together like we did when we were young. Staying at our eldest sister’s place, I felt like that wish came true. The long journey is over now, and it’s time to return to where I belong.”

Supported by her husband, my youngest sister walked back home with determination. Like the rapid descent of darkness after daylight saving time ends, the disease progressed swiftly after the diagnosis. Our hour-long calls have now shortened to barely ten minutes. Yet, whether sitting or lying down, we still breathe together. We inhale and exhale while listening to the apartment announcements from my youngest sister’s home, the sound of dishes being washed at my eldest sister’s place, and, if we’re lucky, the voices of our nieces and nephews. Simply sharing time together—we connect with one another.

“My sister is sick.” Those words are difficult to say. My silence feels like it traps her in pain, making me restless. Yet, I also fear that voicing it lightly will bring unbearable guilt, so I swallow my words once again. I lay them down here now, perhaps because of the faces of my sisters that lingered on every object I encountered on that boat that day, because of the joy of life that overflowed even amidst sorrow. Or perhaps, it is because of the poem I found in Kiki’s thesis.

Because I have no choice but to lean on those eyes that read movement within stillness and those fingertips that detect the slightest vibrations and tremors.

*

Becoming an audience means adopting a certain stance—it is the act of observing and recognizing that something is happening. I look at the afternoon view from the living room while I stay at Kiki’s house. I listen to her neighbors sitting in the Turkish bakery downstairs. I watch the trees swaying outside the window and the fluttering wings of birds in their nests. I become part of the exhibition, I become part of her home.

In the meantime, words are exchanged and memories are mixed. Moon said that he found himself in Kiki’s writings. Arriving there while leaving here, arriving here while leaving there, the state on the plane, communing with the birds that come near the window, even the pain in Kiki’s shoulder that made her stop… He said he read them all as if they were his own stories.

I stood up and asked for an autograph on the thesis booklet. Kiki sat on the floor, folded her knees to one side, held a pencil, and lowered her head. It looked like a neat stone tower.

Observing Lacuna

The scenery has changed

While everything was moving

There is nothing which stands still

Every-thing moves its body

Doesn’t have to be a dance

Doesn’t have to be a walk

Doesn’t have to be shaping clay

Everything is already moving

The whole willow shivers its body by a little touch of wind

Our voice shivers when we try to choose words for real

Our shoulders shrink when we talk about our friend’s death

Our lips make subtle bow

When we notice a leaf is landing on the ochre leaf

When we see two bugs are cuddling cheeks

When we notice the tow trees have been hugging each other for decades

There comes a gentle wave on our foreheads

When we are looking into these things

Our hears start to break into pieces

Pieces of thousands of leaves

Pieces of puzzles on the water

When we sit and look for real

“I read the fortune telling that I will get my body back this year. I often repeat that cryptic yet comforting phrase to myself. These days, I spend time in Gangwon-do. I wake up in the morning, run along the winding river, and sweep up the fallen leaves that pile up in the yard every day…”

I recall Kiki’s Instagram post where the phrase ‘A Year in Search of Body’ first appeared. The sunlight of Gangwon-do, the winding waterway, and the solid pebbles seemed to reveal themselves all at once. Even in the stone tower lying on the ground, I also find Kiki’s body breathing like a landscape.

“But why do we have to close it?” It was only after a while that I asked the question I was curious about when she said, “It is important to close the door on the lake.” “Because the place we are is here and now,” Kiki replied.

I also asked about the day she wrote the poem.

“The class that day was held in Tiergarten. We each practiced looking quietly in the forest for 30 minutes. I wrote that after returning from that moment of observing.”

Once again, what struck me was the act of returning. Closing the door is just as important as opening it. There are paths that can only open once they are closed.

Graduation.

<A Year in Search of Body> is Kiki’s graduation exhibition.

Congratulations on your graduation!

답글 남기기